In a previous blog I decided to critique some creationist blogs, one of which was by a feller called Daniel Mann. To see my first critique of his blog, see

here. I occasionally see his other posts and wonder if I should respond to them, though I then decide that it is better not to. I've discussed with him before, he tends not to pay much attention. Earlier today I noticed that he has posted twice in the last couple of days on evolution, one blog attacking the theory, the other attacking theistic evolution. Naturally I struggled to resist, so here I am.

The Wonders of Evolution

Mann's blog criticising evolution,

The Wonders of Evolution, explores the principle of optimisation, where nature contains systems which are as functionally optimal as possible - they just could not get any better. He quotes from an article in the New York Times which mentions photoreceptor cells as an example, along with many other excellent examples. This single aspect of the eye does seem to be functionally optimal, but this does not mean that eyes as a whole are functionally optimal. His reasons for discussing these are encapsulated in this statement:

Obviously, these findings do not point to the expected messiness of a mindless evolutionary process.

Personally I do not see why messiness must be expected in evolution, it is just that evolution can account for it occurring due to its often co-optive nature - it must use what is available and that sometimes involves cobbling something together, as long as fitness is increased. When the variation is available then co-option might not occur, allowing for the possibility of optimal function. So what we should expect from evolution is a mix, where some functions are examples of co-option and exaptation (the now eponymous panda's thumb for example) and some have achieved functional optimality. If something can be altered quantitatively rather than qualitatively, in other words tweaked bit by bit a degree at a time, then resulting in the optimum is not difficult. Mann continues:

In fact, evolutionists have always been ready to capitalize on any findings that might demonstrate the sloppiness of an evolutionary process: “You see, here’s evidence for evolution. Just look at the vestigial organs (useless organs left-over from prior stages in our evolutionary past)!”

A sloppily constructed adaptation becomes evidence for evolution when the alternative is design by an omnipotent and omnibenevolent Creator. If a human designer could do better, why should we think that the omnipotent Designer would do the same? A vestigial organ, contrary to what Mann thinks, is one which does not serve its proper function, as opposed to one which is completely functional. Mann then goes from vestigial organs to that other creationist favourite, junk DNA:

Then you heard about “junk DNA,” our useless sets genetic baggage bequeathed to us by our former relatives! Well, now they don’t look so junky after all. Science has found that they do have a function. However, finding leftovers and junk is just the thing that the blindness and messiness of evolution would expect to find.

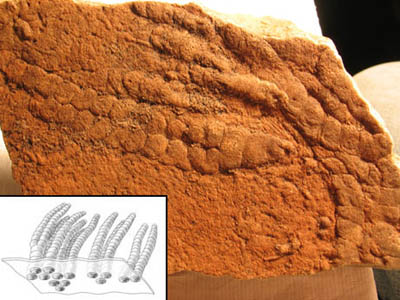

Mann is not completely wrong, but misses the mark significantly. Many areas of junk DNA do have functions which have recently been discovered, but what Mann is doing is selective reading. Junk DNA does not necessarily serve no function, it does not code for proteins, which is how we recognise it. Further to this, there are many areas of junk DNA which are both functionally useless and provide great evidence for evolution, such as pseudogenes and retroelements. Mann has lumped all junk DNA together and ignored the differences within. He then goes on to do the same with the eye, taking the optimally functioning photoreceptors and ignoring the whole.

Overall, his argument was sorely disappointing.

How Does Evolution Give Glory to God?

“While I agree with you that science reveals to us the glory of God (Romans 1; Psalm 19), the same doesn’t hold true for the theory of evolution. Evolution instead says, ‘Mindless, purposeless processes have created what you see around you.’ As such, it deprives God of His glory!! Please don’t confuse the two things—science and evolution!”

Ironically it is Mann embracing confusion by conflating atheistic interpretations of evolution with the theory itself. Evolution does not say 'mindless, purposeless processes' as that is a metaphysical claim, beyond what science can say. It is a valid understanding, but of equal validity with a Christ centred view, such as that which Kathryn Applegate (from the video he is responding to) espouses in response to Mann:

I don’t see evolution as mindless and purposeless at all - rather God is intimately involved in the process by His providential upholding of creation, just as He is in our lives... A thoroughly God-centered view of evolution is elegant, beautiful, and intellectually satisfying. We are fearfully and wonderfully made!

In his response to Applegate, Mann continues to misunderstand evolution and how God acts. He sees the randomness of mutation, along with natural selection, as incompatible with God. The randomness of mutation is observable and there are numerous possible theological responses formulated centuries ago to answer this. When taken with natural selection we get evolution, so as selection is not random neither is evolution as a whole. Having an issue with natural selection baffles me, for why can the acts of nature not also be the acts of God? Or why can nature not have autonomy?

Mann's criticisms of theistic evolution lack any theological vigour, they are based on utter misunderstandings of both the theory of evolution and theistic evolution.